Structure and Conversion of Bibliographic Records to ISO 2709

Original Author: Satya Ranjan Sahu (NCSI - Indian Institute of Science) Context: This document details the internal structure of the exchange format used by libraries (ISO 2709) and presents methodologies for converting text data into this format.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Bibliographical information plays an important role in the research community, particularly in the field of science and technology. However, problems often arise during the exchange of bibliographical information, especially when the interchange occurs via magnetic tape or CD-ROM.

Different International organizations such as UNESCO/PGI, UNISIST, ICSU-AB, IFLA, and ISO have taken many steps towards the standardization of Bibliographic Exchange formats. The process of standardization follows a set of codes given by the International Standard Organization (ISO).

The three major purposes of standardization are:

- To permit the exchange of bibliographic records between groups of libraries and abstracting/indexing services.

- To permit a bibliographic agency to manipulate bibliographic records received from both libraries and abstracting/indexing services.

- To serve as the basis of a format for an agency's own bibliographic database by providing a list of useful data elements.

Converting a text file into a standard format such as ISO 2709 has many benefits. For example, the set of programs can be used for indexing and retrieval. This report describes the set of programs developed in C language to convert sample records extracted from a database to a Standard text file.

Chapter 2: File Formats for Exchange of Bibliographic Data

Different file formats for the exchange of bibliographic data came into existence when organizations investigated the feasibility of producing catalogue data in machine-readable form. Exchange formats were developed in parallel with computers to facilitate data transfer.

Some of the major formats developed at International and National levels include:

MARC (MAchine-Readable Cataloguing)

A format standard for the storage and exchange of bibliographic records and related information in machine-readable form. All MARC Standards conform to ISO 2709:1996.

UKMARC

The standard developed, managed, and promoted by the British Library. It is applied in its bibliographic products and services and by many UK libraries.

MARC 21

Formerly USMARC and CANMARC. These standards are maintained by the Library of Congress in consultation with user communities. Since 1995, the British Library has followed a policy of limiting divergence between MARC 21 and UKMARC.

UNIMARC

The primary purpose of UNIMARC is to facilitate the international exchange of data in machine-readable form between national bibliographic agencies. It allows national agencies to use their own national MARC format while using UNIMARC for exchange.

CCF (Common Communication Format)

Prepared with the support of UNESCO. The chief purpose is to provide a detailed and structured method for recording mandatory and optional data elements for exchange between two or more computer-based systems. The structure conforms to ISO 2709.

Chapter 3: ISO 2709

Format for Bibliographic Information Interchange on Magnetic Tape

This International Standard specifies the requirements for a generalized exchange format that will hold records describing all forms of material capable of bibliographic description.

- It does not define the length or content of individual records.

- It does not assign any meaning to tags, indicators, or identifiers.

- These specifications are the functions of an implementation format (like MARC or CCF).

This standard describes a generalized structure, a framework designed specifically for communications between data processing systems.

Principles and Coding

The standard ISO 2709 (standard AFNOR NF Z 47300, December 1987) makes it possible to present any structured bibliographic record in a large variety of formats.

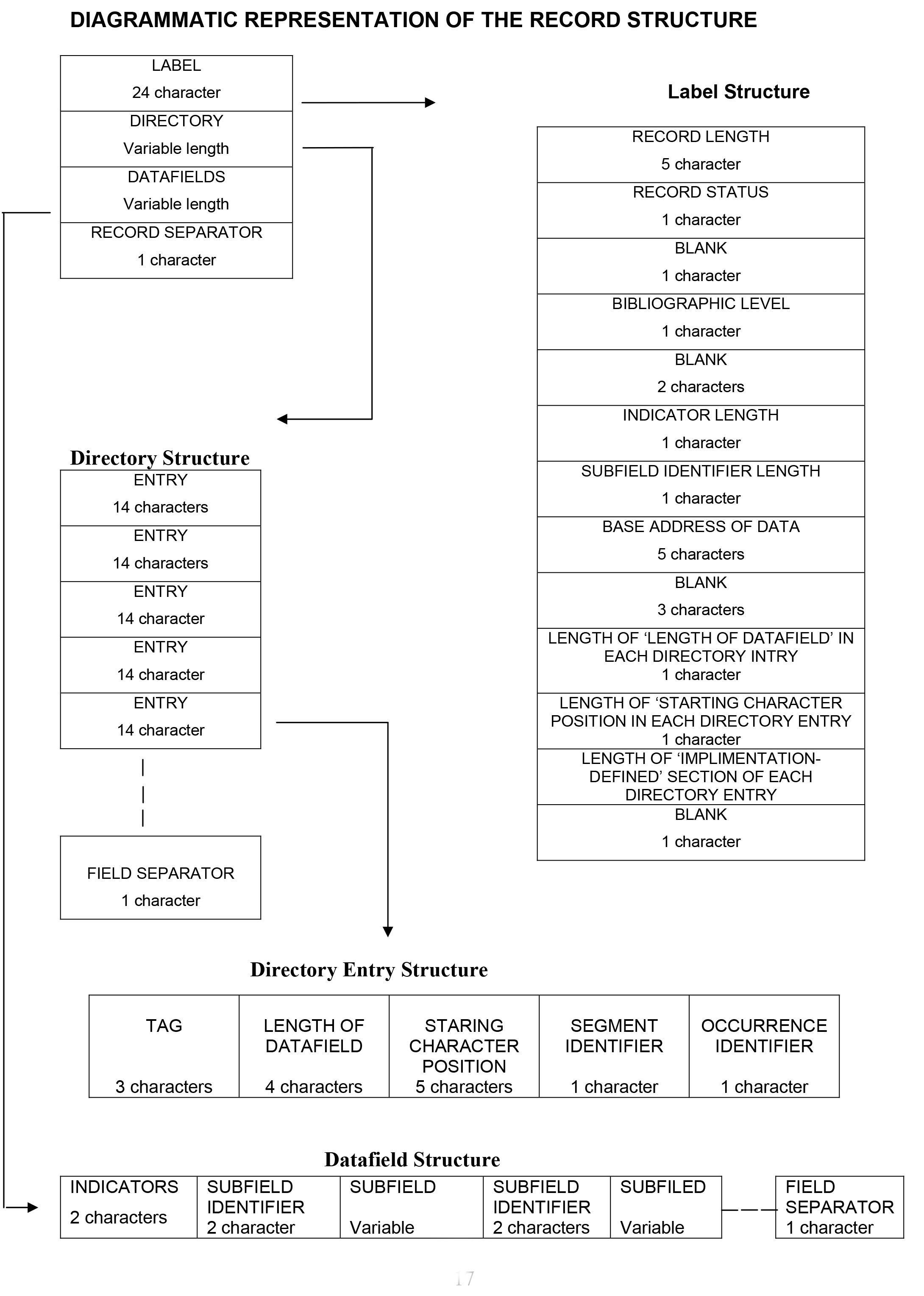

A record in ISO 2709 comprises the following parts:

- Record Label (Leader): Fixed length (24 characters).

- Directory: A variable succession of numerical entries.

- Data fields: The bibliographic data itself.

- Record Separator: Delimiter.

Chapter 4: Structure of Communication Format

The general structure of a bibliographic record consists of four major parts.

1. Record Label

Each bibliographic record begins with a fixed-length label of 24 characters.

| Position | Length | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| 0-4 | 5 | Record Length: Total length of the record (Label + Directory + Data + Separators). |

| 5 | 1 | Record Status: Code indicating status (e.g., New, Modified). |

| 6-9 | 4 | Implementation Codes: Type of record, bibliographic level, etc. |

| 10 | 1 | Indicator Length: Number of characters in the indicators (usually 2). |

| 11 | 1 | Subfield Identifier Length: Usually 2 (e.g., ^a). |

| 12-16 | 5 | Base Address of Data: Location where the first data field begins (relative to the start of the record). |

| 17-19 | 3 | Implementation Defined: Encoding level, cataloging form. |

| 20 | 1 | Length of "Length of Field": In directory (usually 4). |

| 21 | 1 | Length of "Starting Position": In directory (usually 5). |

| 22 | 1 | Length of Implementation Section: In directory (usually 0). |

| 23 | 1 | Reserved: Undefined. |

2. Directory

The directory is a table containing a variable number of entries. Each entry corresponds to a specific data field in the record. The directory is terminated by a Field Separator character.

Directory Entry Structure (12 or 14 characters):

| Part | Length | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Tag | 3 chars | Identifying the field (e.g., 100, 245). |

| Length of Field | 4 chars | Length of the data field (including indicators and delimiters). |

| Starting Position | 5 chars | Position of the first character of the field relative to the Base Address. |

| Implementation | Variable | Segment/Occurrence identifiers (optional). |

Example Entry: 100 0033 00289 (Tag 100, Length 33, Start 289).

3. Data Fields

A data field consists of:

- Indicators: Two bytes (if defined in the Label).

- Subfields: Data divided by subfield identifiers (e.g.,

^a). - Field Separator: The final character of every data field.

Example Data Field:

10^aStephenson^bBM^c1975-#

(Where # represents the Field Separator)

4. Record Separator

The record separator constitutes the final character of the record. It follows the field separator of the final data field.

Diagrammatic Representation (ISO 2709)

Chapter 5: Advantages of ISO 2709

ISO 2709 is documented to ensure consistency in materials, products, processes, and services. Its advantages include:

- Standardization: Provides a small number of mandatory data elements recognized by all sectors of the information community.

- Flexibility: Accommodates varying descriptive practices through variable-length fields.

- Local Needs: Provides optional elements useful for the specific practices of the creating agency.

- Independence: Provides a mechanism for linking records and segments without imposing uniform practice on the originating agency.

Chapter 6: Statement of the Problem & Objectives

Aim: To convert Bibliographic Records into ISO 2709 format.

Need of the Project: Institutions (like NCSI) subscribe to various bibliographic databases (BIOSIS, INSPEC). To provide value-added services, data must be extracted from these databases and built into a local indexing and retrieval system (like CDS/ISIS). Converting this data to ISO 2709 allows the use of standard tools for import.

Limitations: The specific program developed works with "Current Content" database formats, though the logic is general.

Chapter 7: Implementation and Methodology

Converting a text file into ISO 2709 is a complex task. A utility in C language was developed to standardize the text file and convert it.

Standardization Steps

Before conversion, the input text file must be standardized:

- Tag Position: Tags must begin in the same column in each line.

- Tag Format: Tags should be three digits (e.g., expand

1to001). - Data Position: Data should begin at a fixed column.

- Continuation: Multi-line data must respect indentation.

- Record End: Each record must end with a specific delimiter (e.g.,

##).

Conversion Logic (Utility)

- Prompt user for column positions (Start of Tag, Start of Data).

- Prompt for Input Filename.

- Read the input text file record by record.

- Identify fields and map them to ISO structure.

- Calculate offsets and lengths for the Directory.

- Construct the Leader.

- Write the output to

ISO.MST(or.iso).

Chapter 8: Conclusion

The developed program successfully converts "Current Content" data. It can be generalized to convert records from different databases by adjusting the parsing logic. This allows researchers to import text-based bibliographic data into database management systems like CDS/ISIS or ABCD.

Appendices

Appendix I: Sample Input Record (Text)

Authors: MJ Smekens, PH vanTienderen

Title: Genetic variation and plasticity of Plantago coronopus under saline conditions

Full source: Acta Oecologica, 2001, Vol 22, Iss 4, pp 187-200

Author keywords: salt adaptation; Plantago coronopus; phenotypic plasticity

Discipline: Environment / Ecology

Document type: Article

Language: English

Address: van Tienderen PH, Netherlands Inst Ecol...

Publisher: Gauthier-Villars/Editions Elsevier...

Abstract: Phenotypic plasticity may allow organisms to cope...

##

Appendix III: Conversion Code (C Language)

Note: The code below has been reconstructed from the OCR text to represent the logic of the TXT2ISO utility described in the thesis.

# include <stdio.h>

# include <stdlib.h>

int get_field(char line[]);

FILE *fp,*fpt;

main()

{

char str[2056];

char ch;

char strsub1[]="Authors\t";

char replace1[]="300 ";

char strsub2[]="Title\t";

char replace2[]="200 ";

char strsub3[]="Full source\t";

char replace3[]="020 ";

char strsub4[]="Author keywords\t";

char replace4[]="620 ";

char strsub5[]="KeyWords Plus\t";

char replace5[]="625 ";

char strsub6[]="TGA/Book No.\t";

char replace6[]="011 ";

char strsub7[]="Discipline\t";

char replace7[]="610 ";

char strsub8[]="Document type\t";

char replace8[]="060 ";

char strsub9[]="Language\t";

char replace9[]="040 ";

char strsub10[]="Address\t";

char replace10[]="330 ";

char strsub11[]="ISBN/ISSN\t";

char replace11[]="101 ";

char strsub12[]="Publisher\t";

char replace12[]="400 ";

char strsub13[]="Abstract\t";

char replace13[]="600 ";

char field[15];

int i=0,count=0,j=0,l=0,space_count,comma_count;

fp=fopen("ag100.txt","r");

fpt=fopen("new.txt","w");

fgets(str,2056,fp);

str[strlen(str)-2]='\0';

while(!feof(fp))

{ switch(get_field(str) )

{

case 0:

break;

case 1:

space_count=0;

if(strstr(str,strsub1))

{

fputs(replace1,fpt);

fputs("^f",fpt);

for(j=8;str[j]!='\0';j++)

{

if(str[j]==',')

{

ch='%';

fputc(ch,fpt);

j++;

}

if(str[j]==' ')

{

space_count++;

if(space_count==1)

{

j++;

fprintf(fpt,"^l");

}

else if(space_count==2)

{

j++;

fprintf(fpt,"^f");

}

else if(space_count==3)

{

j++;

fprintf(fpt,"^l");

}

else

{

j++;

fprintf(fpt,"^");

}

}

fputc(str[j],fpt);

}

fputc('\n',fpt);

} count++;

break;

case 2:

if(strstr(str,strsub2))

fprintf(fpt,"%s",replace2);

split_rec(str,6);

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case 3:

comma_count=0;

if(strstr(str,strsub3))

{

fputs(replace3,fpt);

for(j=12;str[j]!='\0';j++)

{

if(str[j]==',')

{

comma_count++;

if(comma_count==1)

{

j+=2;

fprintf(fpt,"\n440 ");

}

else if(comma_count==2)

{

j+=2;

fprintf(fpt,"\n490 ^a");

}

else if(comma_count==3)

{

j+=2;

fprintf(fpt,"^b");

}

else

{

j+=2;

fprintf(fpt,"^c");

}

}

fputc(str[j],fpt);

}

}

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case 4:

if(strstr(str,strsub4))

fprintf(fpt,"%s",replace4);

split_rec(str,16);

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case 5:

if(strstr(str,strsub5))

fprintf(fpt,"%s",replace5);

split_rec(str,14);

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case 6:

if(strstr(str,strsub6))

{

fputs(replace6,fpt);

for(j=13;str[j]!='\0';j++)

{

ch=str[j];

fputc(ch,fpt);

}

}

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case 7:

if(strstr(str,strsub7))

{

fputs(replace7,fpt);

for(j=11;str[j]!='\0';j++)

{

ch=str[j];

fputc(ch,fpt);

}

}

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case 8:

if(strstr(str,strsub8))

{

fputs(replace8,fpt);

for(j=14;str[j]!='\0';j++)

{

ch=str[j];

fputc(ch,fpt);

}

}

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case 9:

if(strstr(str,strsub9))

{

fputs(replace9,fpt);

for(j=9;str[j]!='\0';j++)

{

ch=str[j];

fputc(ch,fpt);

}

}

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case 10:

if(strstr(str,strsub10))

fprintf(fpt,"%s",replace10);

split_rec(str,8);

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case 11:

if(strstr(str,strsub11))

{

fputs(replace11,fpt);

for(j=10;str[j]!='\0';j++)

{

ch=str[j];

fputc(ch,fpt);

}

}

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case 12:

if(strstr(str,strsub12))

fprintf(fpt,"%s",replace12);

split_rec(str,10);

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case 13:

if(strstr(str,strsub13))

fprintf(fpt,"%s",replace13);

split_rec(str,9);

fputc('\n',fpt);

break;

case -1: //printf("13%s",str); // to handle failure to match a field //

fprintf(fpt,"##\n");

} // end of switch //

fgets(str,2056,fp);

str[strlen(str)-2]='\0';

}

fclose(fp);

fclose(fpt);

}

/*====================================*/

int get_field(char line[])

{

int num=0;

char field[15]="";

char allfields[15][16]={"Record",

"Authors",

"Title",

"Full source",

"Author keywords",

"KeyWords Plus",

"TGA/Book No.",

"Discipline",

"Document type",

"Language",

"Address",

"ISBN/ISSN",

"Publisher",

"Abstract"

};

for(num=0;num<14;num++)

{

if( strncmp(line,allfields[num],strlen(allfields[num]))==0 )

{

return num;

}

}

//printf("NOT FOUND!\n");

return -1;

return(-1); // to indicate failure to match any of above fields //

}

split_rec(field_value,start_posn)

char field_value[];

int start_posn;

{

int m,i,j,k,len,printed;

char fld_val[86];

i=k=m=len=printed=0;

j=0;

fld_val[0]='\0';

len=strlen(field_value);

for (i=start_posn;i<=len;i++)

{

fld_val[j]=field_value[i];

j++;

printed=0;

if(j>75)

{

fld_val[j]='\0';

j=0;

if(m==0)

{

fprintf(fpt,"%s\n",fld_val);

printed=1;

m=1;

}

else

{

fprintf(fpt," ");

fprintf(fpt,"%s\n",fld_val);

printed=1;

}

//printf("\n%s:",fld_val);

fld_val[0]='\0';

/*printf("press enter to continue: ");

getc(stdin);*/

}

}

if(!printed)

{

if(m==0)

{ fprintf(fpt,"%s",fld_val); }

else

{ fprintf(fpt," %s",fld_val); }

}

}

SAMPLE RECORD:

026280000000002050004500300003300000200007900033020005100112440000

500163490002800168620005900196625013100255011000600386610002200392

060000800414040000800422330009600430101001000526400007100536600181

500607#^fMJ^lSmekens%^fPH^lvanTienderen#Genetic variation and plasticity of

Plantago coronopus under saline conditions#Acta Oecologica - International Journal

of Ecology#2001#^aVol 22^bIss 4^cpp 187-200#salt adaptation; Plantago

coronopus; phenotypic plasticity#PHENOTYPIC PLASTICITY; REACTION

NORMS; SALT TOLERANCE; LIFE-HISTORY; EVOLUTION; LIMITS; GROWTH;

POPULATIONS; ALLOCATION; SELECTION#488NK#Environment /

Ecology#Article#English#van Tienderen PH, Netherlands Inst Ecol, Ctr Terr Ecol,

POB 40, NL-6666 ZG Heteren, NETHERLANDS#1146-609X#GauthierVillars/Editions Elsevier, 23 RueLinois, 75015 Paris, France#Phenotypic plasticity

may allow organisms to cope with variation in the environmental conditions they

encounter in their natural habitats. Salt adaptation appears to be an excellent

example of such a plastic response. Many plant species accumulate organic solutes

in response to saline conditions. Comparative and molecular studies suggest that

this is an adaptation to osmotic stress. However, evidence relating the physiological

responses to fitness parameters is rare and requires assessing the potential costs

and benefits of plasticity. We studied the response of thirty families derived from

plants collected in three populations of Plantago coronopus in a greenhouse

experiment under saline and non-saline conditions. We indeed found a positive

selection gradient for the sorbitol percentage under saline conditions: plant families

with a higher proportion of sorbitol produced more spikes. No effects of sorbitol on

fitness parameters were found under non-saline conditions. Populations also

differed genetically in leaf number, spike number, sorbitol concentration and

percentages of different soluble sugars. Salt treatment led to a reduction of

vegetative biomass and spike production but increased leaf dry matter percentage

and leaf thickness. Both under saline and non-saline conditions there was a

negative trade-off between vegetative growth and reproduction. Families with a high

plasticity in leaf thickness had a lower total spike length under non-saline

conditions. This would imply that natural selection under predominantly non-saline

conditions would lead to a decrease in the ability to change leaf morphology in

response to exposure to salt. All other tests revealed no indication for any costs of

plasticity to saline conditions. (C) 2001 Editions scientifiques et medicales Elsevier

SAS.##